Contains spoilers for Buffy and Angel. Not the comic books, though. Those never happened.

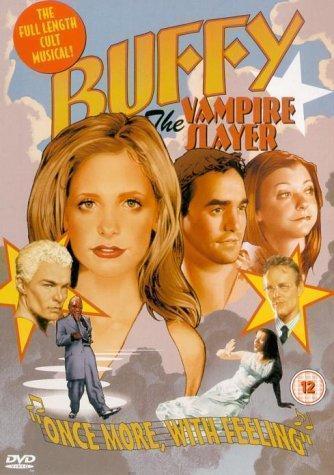

Buffy

the Vampire Slayer was famously

asking the question: what if, in a typical horror-movie

monster-chases-girl scenario, the girl turned around and kicked the

monster's ass? But it's also, perhaps less wittingly, asking the

question: what happens when an atheist – someone who disavows the

existence of all things super- or preternatural in the real world –

writes a show about the supernatural?

Of

course, American TV, and especially the WB in the late 90s, is

perhaps not the best forum for a nuanced discussion of faith and

religion. Even so, it's striking how one-dimensional the perspectives

on the supernatural are on Buffy.

Maybe I know too many seminarians (I know a lot of

seminarians), but it seems very odd to me that nobody we know in

Sunnydale reacts to the presence of demons and vampires by turning to

religion. Especially once the show's mythos expanded to encompass an

elaborate lore of gods, resurrection, heaven and hell, and de- and

re-ensouling, the big G remains notable for its total absence. Even

after experiencing a heavenly afterlife, Buffy's only comment about

God's existence is “Nothing solid” (S7E7, “Conversations With

Dead People”). And I for one would find this profoundly

unsatisfying. Once you have come across the First Evil (as worshiped

by an ex-priest, no less!), would your first question not be: So is

there an equivalent primordial good?

On

a metatextual level, of course, this all makes perfect sense. The

premise of the show is not God, religion, or Manichean

dualism fought on a cosmic scale. Metatextually, we know that the

Buffyverse is a world where the supernatural forces of evil operate,

but the question of God is moot, and the source of goodness is

people's love for each other and their willingness to make sacrifices

for the sake of what's right. From the perspective of a viewer

looking in on this world, we can accept this, but once we try to

imagine ourselves truly inside the Buffyverse, the cracks in its

metaphysics begin to appear.

These

cracks show themselves most clearly in late-period Buffy,

when the series starts to sink under the weight of its own mythos.

The show, which had once so brilliantly and wittily allegorized the

trials of growing up as horror-movie monsters, lost its focus and its

direction in the final two seasons. Buffy tries

not to simplistically equate soul with good and soulless with bad,

attempting to explore gray areas and moral ambiguities, but this

winds up pulling the show in hopelessly contradictory directions: if

vamps and demons have the potential to be good, if they are

redeemable to the point of being able to want a

soul, then how is Buffy justified in constantly staking them? Add

what we learn from Angel,

and things get even less coherent. If ensoulment and

goodness/evilness are, as Angel the

supposedly more grown-up show would have us believe, much more

complicated than that, how come Angel yo-yos between Good, ensouled

Angel and Evil, soulless Angelus with, frankly, comical facility?

|

| Come on, it's a bit silly. |

When

Darla, staked as a soulless vampire, is brought back as a human, the

soul question gets even more inexplicable. If, as established very

early on, “When you

become a vampire, the demon takes your body, but it doesn't get your

soul” (Buffy S1E7,

“Angel”), then why does the resurrected human Darla even remember

her life as a vampire? Is the vampire a new, evil creature occupying

the formerly ensouled body, whose soul is now at peace (as that line

of Angel's would seem to suggest); or is it the same person, the same

consciousness, with some fundamental part removed? Is the soul the

individual's consciousness, their moral compass, an ineffable that

somehow endows humanness? What, finally, is a soul?

This

is, of course, a hugely complex question, to which I do not expect a

coherent real-world answer. In a TV show, however, where the quality

of ensouledness apparently determines whether you deserve to live or

die – whether or not it's morally acceptable for our protagonist to

kill you – we damn well need our terms defined.

|

| This is... what a soul looks like? |

Perhaps

this kind of moral and metaphysical incoherence is simply an

inevitable result of the Chosen One narrative. (I'm reminded

irresistibly of Harry Potter,

and of the fan

critiques

that read Dumbledore as a nasty, manipulative figure who deliberately

programs Harry to do his bidding, rather than as the wise and kindly

mentor Harry sees. There are counter-readings of the Bible that find

traditional atonement theory similarly abhorrent, arguing that only

an abusive God would sacrifice his own son.) Noting the

Powers-That-Be who guide events on Angel,

I wonder to what extent it's possible to engage questions of Chosen

Ones, prophecies, destiny and so on without resorting to a Calvinist

determinism.

Naturally

there is a metatextual Calvinist element – it's called the writers'

room – and Whedon occasionally nods to this. Of Buffy

S6E17, “Normal Again,” he

has said: “the entire series takes place in the mind of a

lunatic locked up somewhere in Los Angeles, if that’s what the

viewer wants.” In that same interview he admits that the role of

the soul in the Buffyverse is often simply a matter of narrative

convenience; and that, I think, is kind of cheating. When we watch a

show, our assent to its premise is a kind of contract: we will accept

this premise, provided that the show does not flout the narrative

rules on which it is predicated. If a show flouts its own narrative

rules – say, retconning

an entire season as a dream – audiences tend to feel that the

contract has been violated. Altering something as crucial to the

show's whole premise as the function of the soul according to

narrative diktat is, I think, a similar violation.

As

a lover of Buffy and a

theologian, I want Buffy to

be theologically and metaphysically coherent. I want it either

to establish one metaphysical system as true for the world it

portrays, or to

represent a believable variety of beliefs among its characters. The

former is an entirely lost cause; the latter is frustratingly

undercooked. Willow's Judaism is wholly Informed,

and her turn to Wicca is entirely to do with magic. There is no

sense at all of Wicca (or any other religion) as an ethical code,

as a way of making meaning, as a way of personally relating to the

world and others in it.

Ultimately,

this is the same problem I have with the show's self-professed

feminism. Joss Whedon is a proud feminist, and yet in the course of

Buffy some very

unfortunate tropes appear – Bury

Your Gays, Psycho

Lesbian, No

Bisexuals, Token

Minority, general racefail – which cumulatively suggest a

writers' room that just didn't necessarily see the implications of

everything it was doing, perhaps because it lacked the

diversity of viewpoints necessary to provide checks and balances on

overwhelming privilege. Established metatextually, the show's

feminism is taken for granted by all characters in-universe, and it

requires extra work on the part of the viewer to critique its

problematic elements. Perhaps this fundamental incoherence of Buffy's

feminism is tied to its fundamental metaphysical incoherence. Both

seem to stem from the same failings.

|

| But also, there were really really awesome things. |